Fast fashion is a pervasive issue in the global clothing industry, characterized by the rapid production of inexpensive, trendy garments that are quickly consumed and disposed of.

The fashion industry is responsible for 10% of all global carbon emissions—more than those of the aviation and shipping industries combined— with 85% of textiles ending up in landfills or incinerators. (1) Fast fashion's cyclical destruction and disposal of natural resources are equally alarming. The industry relies on low-cost, labor-intensive practices and cheap materials, which result in over 92 million tons of textile waste generated annually. (2)

As the demand for the latest styles increases, so does the strain on our environment. It is essential to address the ecological and ethical consequences of fast fashion to combat its increasingly damaging impact on our planet.

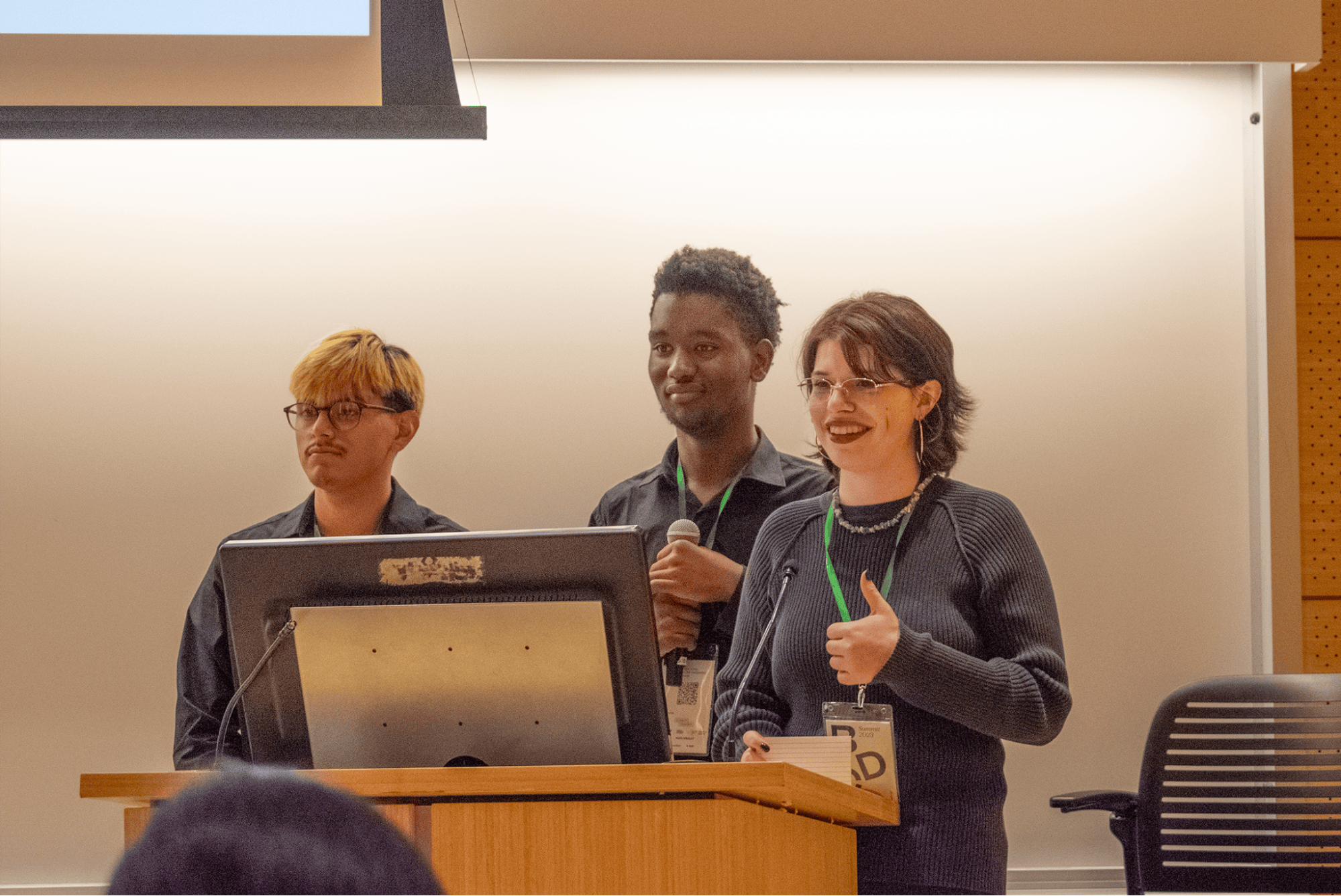

Meet The Team

Josephine, Omar, and Adrian are high school students from Lankenau Environmental High School in Philadelphia.

Josephine Schirling hopes to study climate/environmental change and ecological processes to learn about the systems in place in nature.

Omar Keita is now a freshman at Arcadia University, where he studies biology and close symbiotic relationships between different species.

Adrian Martinez-Monico is currently a freshman at Chestnut Hill College, studying business and entrepreneurship. He hopes to work with companies to implement sustainable and green design practices.

Project Conceptualization

Joining the Biodesign Challenge and the Aula Future design program, Josephine, Omar, and Adrian learned about the idea of regenerative design and explored innovative biodesign concepts that they eagerly incorporated into their project in order to reimagine a more sustainable future.

As the team began researching fashion practices, they discovered the traditional methods of creating clothing from the early nineteenth century. Before the introduction of mass production in the United States, clothing was traditionally handmade and sourced from local, natural resources. The local Pennsylvania Dutch community used the wool of sheep from their own farms to be hand-spun into thread and fabric, and local berries were used for natural dyes, using a fraction of the energy and materials used today for the same end product.

However, the modern fashion industry has long since deviated from these sustainable practices. Fast fashion has led to alarming environmental and social problems, and the team wanted to instead emphasize a local fashion system that opposed modern fast fashion trends and draw from traditional methods of sustainably sourced clothing from nature that employed biological stewardship.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

As students from an environmentally-focused high school, the team had prior experience and knowledge regarding biological systems and were also connected to local environmental centers. They often visited community gardens where they helped with invasive plant management and the upkeep of native plants. It was through this work that they realized the tremendous issues, and, for the purposes of their project, the opportunity that the biomass of local invasive species posed.

Invasive plants are those that out-compete native species and disrupt the natural vegetation, costing the United States more than $423 billion in estimated losses (3). Their unchecked proliferation can lead to a significant loss of biodiversity and damage to existing food systems.

Due to their fast-growing nature, community gardens, and environmental centers typically often manually weed and pull invasive plants out of the ground to protect their native plants. However, rather than their waste being repurposed or utilized in a sustainable manner, it is often entirely discarded in landfills, contributing to the mounting problem of organic waste decomposition and emissions.

The team saw invasive plants as an underutilized biomass that could service their communities. While some efforts have been made to harness the potential of invasive plant waste for bio-energy or other sustainable uses, uses for the vast amounts of invasive plants remain largely unaddressed.

Recognizing the ecological disruptions and waste that invasive plants caused in their own community gardens, the team wanted to repurpose the unutilized waste from discarded invasive plant species to create a fashion collection that would emphasize local natural ecosystems.

Inspired by their new knowledge, the team asked themselves:

“How can we harness invasive plants to reshape the fashion industry, reducing the financial and environmental costs associated with production?"

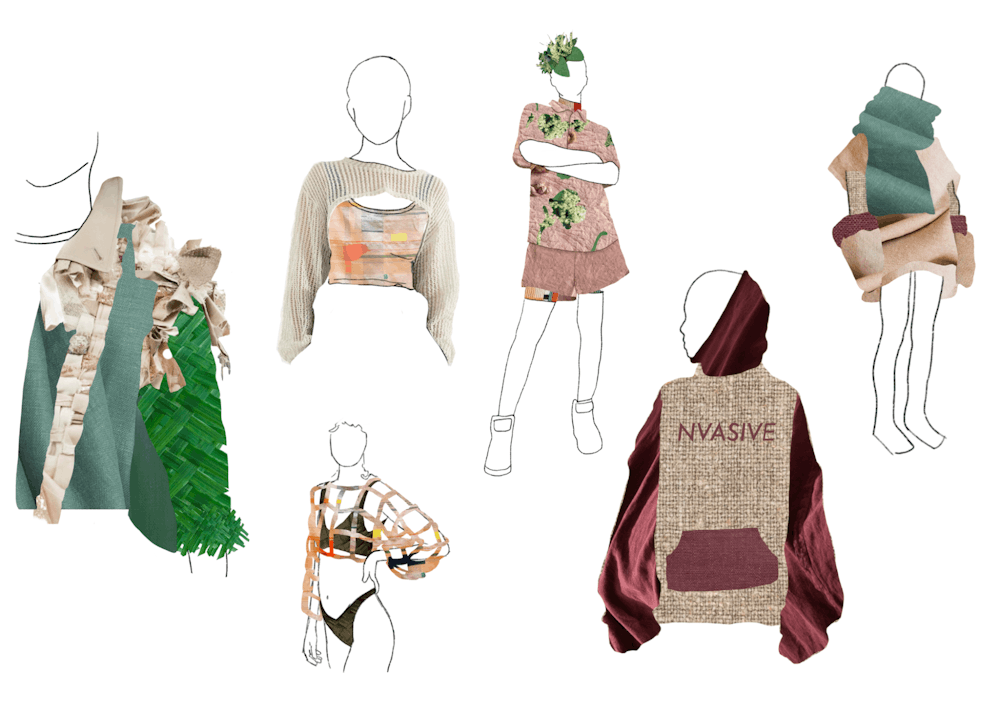

Meet NVASIVE

NVASIVE is a fashion collection that leverages local, seasonal, and underutilized biomass, specifically invasive species found on US soil. Instead of relying on traditional supply chains, NVASIVE taps into the potential of invasive species to create a local, sustainable, and regenerative fashion industry.

The NVASIVE team extensively researched the prevalence of invasive species in their local environment, reaching out to the vast network of environmental centers and experts across the Philadelphia region—including the Discovery Center, Schuylkill Center, and John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge—to gain background information on the subject matter.

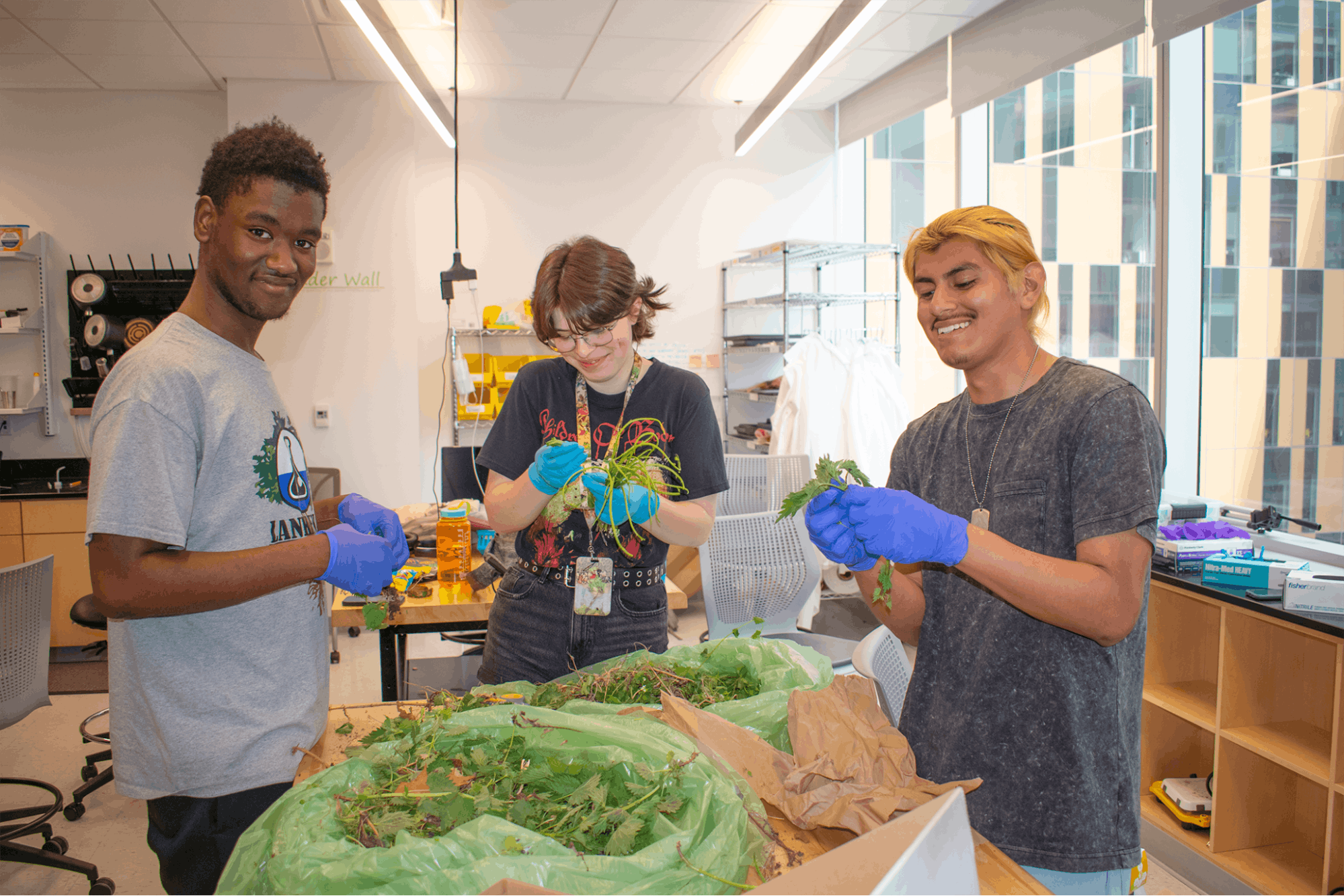

They familiarized themselves with plants found in the Philadelphia area to be able to differentiate native ones from invasive ones. In particular, they noticed the abundance of Japanese knotweed, garlic mustard, and phragmites—all invasive plants that were pulled out and discarded in these environmental centers.

Speaking with Moushira Elamrawy, the founder of Cavani Textiles, which specializes in naturally dyed and agriculture waste textiles, the team discovered the specific properties needed to create fibers and threads such as the presence of cellulose (4). Cellulose is a polysaccharide found in the cell walls of plants and is responsible for its strong structural shape. All plants have different amounts of cellulose which correspond to its strength and sturdiness. Taking this into account, the team discovered that the elevated cellulose levels in the invasive plants they had gathered could be turned into fibers and set upon finding both the best plants and methods for fiber development.

The process of developing fibers was very long and arduous for the team.

NVASIVE spent weeks at local environmental centers and gardens to volunteer and pull out invasive plants from the soil to use as biomass material to develop their project. After collecting copious amounts of Japanese knotweed, garlic mustard, and phragmites, they separated the stems and fibers to loosen their structure. Then, the plants were boiled in hot water to soften the material.

Since Japanese knotweed had a much larger lignin content—a molecule that determines how herbaceous and woody the material is—than the other plants, it resembled bamboo and was extremely tough to process. Through this setback, the team realized that they could use sodium bicarbonate or baking soda to induce a softening effect on the tough fibers. They created a proportion of one cup of baking soda to every ten ounces of plant material, with a pH of 10 to make the solution alkaline and break down the acidic concentration of lignin at a faster rate.

After leaving the boiled plants to dry, the team began the carding process. Equipped with large carding mats, gloves, and wooden carding brushes with metal pin teeth, they spent a lot of time and energy brushing and carding to create softer plant material. After refining the material repeatedly until a level of desired softness was reached, the team was left with soft fibers, colored in natural shades of yellow, green, and brown.

Hoping to expand these natural colors, the team returned to the idea of harnessing invasive plants.

Speaking once again with local environmental experts, they discovered mulberries, an invasive plant species in the Philadelphia area. Mulberries are colored with strong red pigments—a characteristic that the team hoped to utilize to naturally color their fibers. Collecting mulberries from these environmental centers, they used a traditional mortar and pestle to grind the berries and filter the concoction through the mesh of cheesecloth fabric. Now, a solution of mulberry dye was created, suitable to color their plant fibers.

However, during the 6-month research and development phase, the team could not conjure the necessary resources and equipment to create an efficient system to turn their invasive plant fibers into workable thread and final clothing pieces for a fashion collection. Despite this, the NVASIVE team envisioned, mapped, and visualized a process to expand their work in the future.

The necessary infrastructure to create this process already exists and is commonly utilized in the process of creating linen, a similar organic fabric material. As such, they hope to utilize these existing production systems to turn the extracted fibers into fabric and wearable clothing.

In creating these fashion collections sourced from local invasive plants, the NVASIVE team hopes to emphasize locality and the connection with the natural world we live in. Combatting the societal norms of fast fashion and textile waste, NVASIVE serves to create a local and self-sustaining fashion system sourced from local invasive plants and rediscover the traditional practices of creating textiles from unused biomass.

Next Steps

Josephine, Omar, and Adrian hope to continue developing NVASIVE in the future. In particular, they hope to expand the versatility of the invasive plant textile they created to meet additional needs. To truly flourish and actualize their vision, the team identified ways to expand NVASIVE’s goal to create local sustainable fashion systems:

Firstly, the NVASIVE team hopes to collaborate with environmental centers and fashion brands to develop a network to effectively collect and distribute their textiles. They hope to partner up with these community centers and utilize their unused biomass from invasive plants to directly turn them into fabric and clothing, sent to partnered fashion companies.

Secondly, since the textile is extremely versatile, they hope to expand from not only clothing but also to other accessories, such as bags and belts. Invasive plants such as Japanese knotweed and garlic mustard have a texture and appearance similar to canvas, which can be used.

-

Lastly, the team would love to develop seasonal collections to have affordable fashion options available year-round that reflect the changing variety of plant varieties throughout the year.

Conclusion

The development of projects like NVASIVE shares a glimpse of how we can reimagine and reshape industries like fashion and textiles to become more sustainable for future generations.

Fast fashion and textile waste are a growing concern as fashion trends change at an increasingly rapid pace and greater attention is placed on cheap, low-quality clothing items. In the face of these challenges, NVASIVE seeks to transform fashion norms by emphasizing the importance and beauty of naturally sourced clothing options from invasive plants.

Not only does this allow for the emphasis on locality, but it also allows for native plants to flourish in their local environments without the domination of invasive plant species. In short, NVASIVE envisions a future in which the threat of native plants is converted into the principal raw material powering the fashion industry, making both the production of clothing and ecosystems healthier for local and global communities to enjoy.